Museum Exhibits

Welcome to the McCormick Bridgehouse & Chicago River Museum online exhibits. Our online exhibits are designed to complement the Bridgehouse Museum experience for people with disabilities who are unable to climb the stairs at the museum. The first floor and the dramatic gear room are both wheelchair-accessible, however the remaining four floors of the bridgehouse are accessible by stairs only. If you have any questions, please contact us at bridgehousemuseum@gmail.com.

Museum Exhibits - Introduction

Standing Near the Site of the Future Bridgehouse

“The land was a low wet prairie, scarcely affording good walking in the dryest [sic] summer weather, while at other seasons it was absolutely impassable…the usual mode of communication between the fort and the Point was by boat rowed up the river or by a canoe paddled by some skillful hand.”

-Juliette Kinzie, 1862

Prairie stream, bustling port, city sewer, living treasure: the Chicago River

The Michigan Avenue Bridgehouse represents a grand vision for a river and its city.

If you stood at the site of the McCormick Bridgehouse & Chicago River Museum 350 years ago, you would be knee-deep in mud, almost on the lakeshore. To the west you could see miles of prairie; to the east, the sand dunes of Lake Michigan; and across the river, wetlands teeming with life.

From the beginning, the river was vital for trade and travel, providing a connection between the Atlantic Ocean, Great Lakes, and the Mississippi. This strategic link laid the foundation for a booming metropolis—and meant great changes for the Chicago River.

The Original Chicago River

The North and South Branches once flowed into the Main Stem, which emptied into Lake Michigan.

The North Branch originated with three indistinct forks. These forks, called sloughs, were marshy, wet areas with little current.

The South Branch began at Mud Lake, the key to the area’s development. Here, Native Americans traveled between the Des Plaines River (which links to the Mississippi) and the Chicago River (which links to Lake Michigan). Except for the short periods when Mud Lake flooded its banks and connected the two rivers, people portaged it, carrying their canoes and goods over land.

As early as the 1600s, visitors contemplated the value of a canal to replace the portage. Had the Des Plaines and Chicago rivers not been so close and had a mountain—instead of a small hill—separated them, perhaps there might not have been a Chicago.

The River's Watershed

Chicago River Watershed Today. What's a Watershed?

Courtesy of Friends of the Chicago River

The term watershed is used to describe the land that drains to a particular river or other body of water. In the Chicago River watershed, this means that the rain and other water that comes from your home, garden, farm or business has the potential to reach the Chicago River.

The Chicago River's Original Watershed, ca. 1650

Courtesy of Friends of the Chicago River

The Chicago River: A Meandering Prairie Stream

“Arriving at Douglas Grove, where the prairie could be seen through the oak woods, I landed, and climbing a tree, gazed in admiration on the first prairie I had ever seen. The waving grass, intermingling with a rich profusion of wild flowers, was the most beautiful sight I had ever gazed upon…while to give animation to the scene, a herd of wild deer appeared, and pair of red foxes emerged from the grass…I saw the whitewashed buildings of Fort Dearborn sparkling in the sunshine…I was spell-bound and amazed at the beautiful scene before me.”

-Henry E. Hamilton, 1818

Before there were bridgehouses and skyscrapers, the Chicago River flowed slowly and meandered through wetlands, prairies, and wooded areas. And it had flourished for thousands of years.

The river was alive with insects, frogs, and fish. River otters, beavers, and turtles occupied the riverbanks. Squirrels and hawks made the woods their homes, and coyotes and prairie chickens roamed the prairies.

Human occupants—Native Americans, French explorers, and traders—used the river for transportation, trade, and sustenance.

However, after the establishment of Fort Dearborn, rapid settlement radically changed this vista. Westward expansion and the growth of a city caused people to find new uses for the Chicago River, altering its course forever.

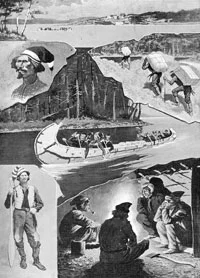

Father Marguette's Winter Quarters, ca. 1670

Courtesy of Chicago Public Library

Chicago, 1820

Courtesy of Chicago History Museum

Standing at Mud Lake

“We remained [in Chicago] about a week to rest our men and prepare for the fatigue and hardships of crossing our boats and goods to the Des Plaines River. Our goods were transported across the prairie on the backs of our boatmen. The boats thus lightened were passed through the eastern outlet of and into Mud Lake…This lake was well named; it was but a scum of liquid mud, a foot or more deep, over which our boats were slid, not floated over, men wading each side without firm footing, but often sinking deep into this filthy mire, filled with bloodsuckers, which attached themselves in quantities to their legs. Three days were consumed in passing through this sinkhole of only one or two miles in length.”

-Gurdon Hubbard, 1818

Nature's Mosaic

The Chicago River watershed sits on an ecological transition zone between western prairies and eastern forests. This zone was once a mosaic of tallgrass prairies, wooded areas, and wetlands. The driving force behind this diverse ecosystem was wildfires. The intensity and frequency of the fires depended on the amount of soil moisture, which in turn determined what vegetation would develop and thrive.

Three hundred and fifty years ago, the vegetation was diverse, and the area teemed with wildlife. Many factors, such as population growth, habitat loss, fire suppression, and invasive species, have vastly changed this landscape.

Ecosystem Map from the Morton

Arboretum

Courtesy of Jeanette McBride–Morton Arboretum.

Looking at the ecosystem map, you will notice that most wooded areas are east of the river and most prairies are west. This trend relates to the critical role of the river in preventing wildfires from spreading.

Prairie fires started from ligning strikes or by deliberate fires set by Native Americans. The fires then spread east with prevailing winds. When fires reached the river, they died out. Forest plants and trees, such as maples, willows, and basswood, were able to survive.

Early Animal Life

Beaver

Beavers were once widespread along the Chicago River, but were almost completely wiped out statewide by the late 1880s. Known by early Europeans as “black gold,” the beaver’s downfall was its excellent coat, which was used to make quality felt for hats, a fashion that lasted 300 years. Today, beaver populations are recovering and property owners near the river wrap their trees with wire to prevent beavers gnawing their trees.

Beaver

Black Bear

Black bears were once found along the Chicago River and throughout the region. One of the last bear hunts took place in Chicago in 1833. Judge John Jean Caton remembered, “The town was thrown into a great commotion by a report that someone had seen a bear [near Madison and Randolph streets]…however, he was soon brought to grief and cut up into small pieces that all in the town who were fond of bear meat might have a taste.”

Black Bear

Eastern Massasaugua

Also known as the swamp rattlesnake, the Eastern Massasaugua was once the region’s most common venomous snake. However, their numbers dwindled due to mass killings and habitat loss. In the late 1820s, a Massasaugua bit Frances Barker, who lived near Chicago. “From that time on we waged wars on snakes. It seems wonderful that we killed them…by putting a piece of timber, or even a foot upon their heads, and holding them down until someone could come and sever or bruise their bodies.”

Eastern Massasaugua

A Land for Many People

Native Americans, such as the Chippewa, Ottawa, Pottawatomi, and Miami, used the Chicago River and its portage for thousands of years. The waterways supplied sustenance for their communities and were lifelines for travel and trade.

For French fur traders, the watershed provided a rich animal population. Traders could portage from the Chicago River to the Des Plaines and onto the Illinois, extending their network. Many explorers crisscrossed the area seeking connections between the Mississippi River and the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Jesuit missionaries, who often traveled with explorers, used the river to reach their converts and missions.

Translation of Regional Native American Words from the Journal of Lemeul Bryant, 1832

Coutesy of Chicago History Museum

Chicago, 1820

Courtesy of Chicago History Museum

Jean Baptiste Point DuSable

Jean Baptiste Point DuSable was an Afro-French fur trader who established a farm at the mouth of the Chicago River in the late 1780s. Considered the “father of Chicago,” he was the area’s first nonnative permanent settler.

Deed of Sale for DuSable's House from DuSable to Jean B. Lalime, 1800

Courtesy of Chicago History Museum

John Kinzie's House, Originally Built and Owned by DuSable, 1832

Courtesy of Joni Marin

Voyageurs

French traders were active in this region in the late 1600s, canoeing goods along the Chicago waterways. Their journals record carrying items such as combs, swanskin, bullets, knives, flour, and sugar.

Voyageur Life, ca. 1680

Courtesy of Illinois Heritage Association

A Changing Relationship

At the dawn of the 19th century, the American government claimed the right to control the river and its portage. Like many before them, these newcomers recognized the river’s strategic location. They also envisioned a great city.

A city needs people, and certain events helped secure the area. In 1803, the military established Fort Dearborn to guard the portage route. In 1816, the Pottawatomi ceded parcels of land along the river. And the Black Hawk War treaty permanently forced most Native Americans from the region by 1832.

Despite the Fort Dearborn Massacre in 1812, land speculators, entrepreneurs, settlers, and laborers headed to Chicago. A population of about 350 in 1833 swelled to almost 30,000 by 1850.

The rapid growth of a city on a swamp meant big changes for the river: commerce, industry, and pollution.

Friends of the Chicago River

“The Chicago River is vastly different than it was at the time of Fort Dearborn and would be unrecognizable to those who lived here then. Yet, it is still home to many of the same plants and animals such as beavers, blue flag irises, and endangered black crowned night herons. Today, they share the river with barges, canoes, and tourists viewing our world famous skyline.

The river will never be a natural prairie stream again, but it can still be a healthy home to a large diversity of plants and animals, a beautiful setting for recreation, and a commercial asset for the region."

-Friends of the Chicago River, established 1979